The God of the Labyrinth - A Solution

September 02, 2024

Some notes on hidden aspects on the short story The God of the Labyrinth, as noted by the author Herbert Quain. Republished with permission.

It is uncommon for an author to pen an explanation of their work. Necessarily, I think, the development of matters belongs very much to you, and not very much so to myself – to that end I shall say nothing on the identity, character, or humanity of R. Likewise on the nature of the mistake of the Watson (for whom we should afford a degree of understanding, if not kindness.) I wrote according to my own beliefs on what had happened. Those beliefs are mine alone. You are afforded yours.

However, there are components of the narrative which are not debatable, but instead can be discerned in the manner of a detective. I thought it best to pen a solution as to how one may arrive at certain truths. In particular, these papers will outline the calculation of the name of the victim.

Firstly, it should be well-known to readers of the story that there is an essential trick to the story; that is, that the detective is wrong about the identity of the killer. One may guess this simply by reading the work; however, many more might read Jorge Luis Borges’ examination of my work, which also reveals the trick.

So, then, if R is incorrect, who is the killer? The victim himself cannot be responsible, by this restriction; the Prefect, Herbert, and Kearsley all are supplied with strong alibis. One may wonder if R herself may then be responsible; but there is actually evidence which points, instead, to a different character. Observe the rug which lies in the Storeroom. When the narrator first travels through the room, they observe four “tracks” crossing the rug. Then, after R and the narrator have crossed the rug later in the story, the rug is observed again – and it has seven tracks across it now, three new ones evident. R and the Watson produced two of these new footsteps. Who produced the third? Given Herbert, Kearsley, and the Prefect are all upstairs, it certainly cannot be them!

This, combined with a number of other pieces of evidence – the set of footprints in the Conservatory, for instance, or the gun in the Library – suggest the presence of another person in the Labyrinth. Some close examination of the circumstances of the Labyrinth itself; the fact that there is only one entrance, which has been locked continuously throughout the narrative (except, surprisingly, at the very end) eliminates the possibility of a surprise intruder. If there is another individual in the Labyrinth, they must be there when R and the Watson arrive at the scene.

There is only one possible candidate, a person which is both clearly established to be present and yet never observed: the victim’s automaton. Consider the case where the inventor completed its construction, and indeed found it to be much more capable than any other automaton. (Thus, when they encountered Kearsley on the street, they would have been telling the whole truth!)

It is not necessary here, but as a simple exercise we can conjure a motive. The inventor, who had a “reputation for cruelty” and a wanton disregard for his own creations, would engender fear and terror, and drive his construction to vengeful self-defense. We can also produce a means. The empty stand for a mannequin in the Drawing Room – which would have been where the automaton was kept – is positioned to the right of the desk. If the automaton had been standing there, it would have been trivial for it to shoot their creator.

Now the case seems closed: we know the who and how, the where and the why. But there remains a further hidden secret in the text: that of the name of the victim.

In order to detail how I had hidden it, I took the liberty of inserting myself into the narrative. It is not subtle that Mr. Quain in the text should be in some way representative of Mr. Quain, the author. And, as he says:

“Herbert, meanwhile, was explaining how a secret answer may be encoded into the movement of a murderer after they committed the fatal deed, using a book code.”

The ‘book code’ here is a fifteen-digit serial number, included in the front of any legitimate printings of the text: CODE NO. 651532411255468. This shall come to be useful later.

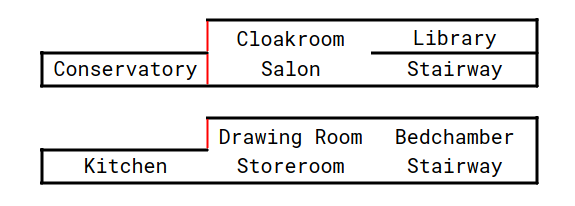

Now we must find the “movement of the murderer” after they committed the fatal deed. This shall involve some mapping. Below, I have marked the outline of all the rooms visited in the course of the narrative, with walls containing framed paintings marked with a thin red line, and all other walls marked in thick black:

There is, of course, an immediate problem. If we believe that the automaton shot its inventor, then where did it go afterwards? Both of its escape routes through the Storeroom and the Bedchamber are cut off by the Prefect and Kearsley respectively. And, when eyewitnesses arrive to the Drawing Room, it is nowhere to be found. It has seemingly disappeared!

To untangle this, we must observe an irregularity. R notes at one point that there are three connections between the top and bottom floors:

“That makes three connections between the lower and upper floors,” the detective said. (I thought she was mistaken but did not correct her.)

There are known connections between the Lower and Upper Stairways, naturally, and the discovered trapdoor between the Kitchen and the Conservatory. But where is the third?

Discovering this requires a little intuition. We know that the Watson discovers a hidden passage behind the painting in the Salon, through the investigation of its hinges. And, earlier, we see R investigating another painting in a similar manner:

I noticed R appraising a still life of bottles to my left; it was hung directly across from a short door to the east. She ran her hand down the right-hand side of the frame, and seemed interested in something.

This, combined with the strange shape of the Labyrinth (there seems to be two missing rooms from the perfect 2x3x2 grid), and coupled with the notepad in the Library mentioning rooms that are never visited, such as the Atelier and the Cellar, may lead to the realization that there are, indeed, two more rooms in the Labyrinth! They must lay behind the still-life painting of bottles and the schematic (in the Cloakroom and the Drawing Room respectively); and they must be connected by a trapdoor, in order to justify R’s comment, and to give the automaton an escape route.

But which lies behind which? It seems foolish to try and assign it based on where these rooms are naturally placed, given how the Labyrinth is confusingly constructed:

It was of great strangeness to have this room so far from the entrance, but this Labyrinth was an odd place all told.

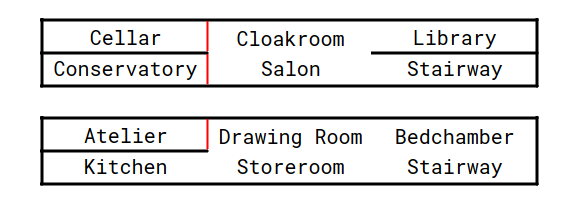

Instead, we might notice that the Conservatory was hidden behind a painting depicting a forest scene, and confidently place the Atelier behind the schematic, and the Cellar behind the painting of bottles.

Now we have a full mapping:

Let’s begin to map out the automaton’s movements. Where do we know that they travel?

Firstly, there is the issue of the gun in the Library. While R does not detect any human sweat or warmth on the handles (as she would not, since it has only been held by a metal automaton), one of the barrels burns her finger:

I took to scanning the rest of the bookshelves as she brushed a finger against the barrels… When I turned back R was sucking her index finger gently, as if it had just been burned, but with the other pointed to the door.

Which means it has recently been fired. Thus, the automaton must visit the Library after the murder is conducted, in order to return this weapon.

There are also the footprints in the Conservatory, going from the Salon to the Kitchen:

The floor was dusty, and a set of footprints led from where I was standing to the center of the room.

And there are the footprints crossing the rug in the Storeroom. Two kinds of footprint cross the rug once in both directions. One must be the Prefect, searching in the Kitchen; but what of the other set of footprints? There are two unaccounted tracks of the same type; one going from the Kitchen, and one going into it. These must be the automaton.

Consider also the movements of the other characters in the Labyrinth. After an investigation in the Drawing Room, the Prefect brings the other guests up into the Salon, to wait. The automaton must therefore not tarry too long in the Library, else they will be trapped, and eventually discovered by R and her assistant.

In order to account for visiting the Library, and passing through the Conservatory once in one direction, the path must therefore start as: Drawing Room -> Atelier -> Cellar -> Cloakroom -> Library -> Cloakroom -> Salon -> Conservatory -> Kitchen.

What next? There are the two tracks across the rug, which implies (at least at the time when the Watson is observing the rug, having just arrived in the Labyrinth) that the automaton must have come out of the Kitchen into the Storeroom, and then returned to the Kitchen. The return makes sense, if the automaton were trying to evade detection from R and the Watson arriving. Likewise, the seventh track (running from the Kitchen into the Storeroom) makes sense, since the automaton must move out of the Kitchen before R arrives there, and must do so by passing through the Storeroom (otherwise they would run into the others in the Conservatory or Salon).

But why would they come into the Storeroom at all? Perhaps they were trying to communicate with Kearsley’s mechanical man:

There was a paper with writing in front of the machine, as if someone had tried to communicate with it.

The precise reason is immaterial. Now we must determine where the automaton went after they came into the Storeroom for a second time. At last we arrive at the issue of the front door; and that it is, when the Watson comes to it again, mysteriously unlocked.

But who can unlock it? Only R has the key. Therefore R must have unlocked the front door at some point, for some reason. And the only effect that doing so would have is to release the automaton from the Labyrinth, so it can escape undetected.

Of note is this particular passage:

R rose, and told me something (to stay there, I would wager); she then went to the north, into the Drawing Room, to confirm her suspicions. At length I heard her talking out loud to herself; gentle footsteps from the north, and then to the east, and the motion of doors; and then the sound of R climbing the stairs.

But what doors are there to open in the room to the east? That room is the Stairway, and the only door there is the front door. R opens and closes the front door at this moment.

So R goes to the north, and speaks. It is no great leap of logic to imagine that she is speaking to the automaton. Then both of them travel into the Bedchamber, and then into the Stairway; and at last R lets the automaton out of the Labyrinth, and then proceeds up the stairs to give the machine its alibi.

Why R would do this is a matter best left to you. But, at last, we have a full path: that of Drawing Room -> Atelier -> Cellar -> Cloakroom -> Library -> Cloakroom -> Salon -> Conservatory -> Kitchen -> Storeroom -> Kitchen -> Storeroom -> Drawing Room -> Bedchamber -> Stairway. A path of fifteen rooms, taken in sequence, that allowed the automaton to pass throughout the Labyrinth entirely undetected, and permit its escape.

Now, with this sequence, the fifteen-digit code comes into play. For each nth digit of the book code, if we take that letter of the nth room in the automaton’s path, we can spell out a name:

| Room | # | Letter |

|---|---|---|

| Drawing Room | 6 | N |

| Atelier | 5 | I |

| Cellar | 1 | C |

| Cloakroom | 5 | K |

| Library | 3 | B |

| Cloakroom | 2 | L |

| Salon | 4 | O |

| Conservatory | 1 | C |

| Kitchen | 1 | K |

| Storeroom | 2 | T |

| Kitchen | 5 | H |

| Storeroom | 5 | E |

| Drawing Room | 4 | W |

| Bedchamber | 6 | A |

| Stairway | 8 | Y |

That name is NICK BLOCKTHEWAY; the hidden name of the victim, and our answer.